The potential role of in-utero Azadirachta indica (AI) dried leaf meal on hepatic function, lipid indices and oxidative balance in offspring of Wistar rats

- Department of Human Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, Baze University, Abuja

- Physiology department, Lagos State University College of Medicine, Ikeja, Lagos

- The Arc of Rensselaer County, New York City, United State

- Department of Science Laboratory Technology, D.S Adegbenro ICT Polytechnic, Eruku-Itori, Ewekoro, Ogun State

Abstract

Azadirachta indica (AI), commonly known as the neem tree, is one of the most widely used herbal plants worldwide. This study explored the potential in-utero role of dried leaf meal (DLM) of AI on hepatic function, lipid indices, and oxidative balance in the offspring of Wistar rats. Eighteen pregnant female and twelve male Wistar rats, weighing between 140 and 180 grams, were used. They were treated with either a normal diet or dried leaf meal (DLM) of AI. The dams were exposed to DLM up to parturition, resulting in treated males and females (TM and TF). Control rats were fed a control diet, comprising male and female rats (CM and CF). On day 70, blood samples were obtained through cardiac puncture to assay liver enzymes: AST, ALT, and ALP. Liver tissues were harvested to assay cholesterol (CHOL), triglycerides (TG), HDL, LDL, hepatic lipase (HL), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT), and malondialdehyde (MDA). The results showed a significant (p<0.05) reduction in liver enzymes, hypotriglyceridemia, LDL-hypocholesterolemia, HDL-hypercholesterolemia, and increased (p<0.05) HL and LPL levels in offspring exposed to AI DLM compared to controls. SOD, GSH, and CAT activities increased significantly (p<0.05) in both male and female offspring exposed to AI DLM compared to controls, with a significant reduction (p<0.05) in MDA, the lipid peroxidation index, in offspring exposed to AI DLM compared to controls. It can be concluded from this study that in-utero A. indica DLM improves hepatic function, lipid metabolism, and oxidative status in the offspring of Wistar rats.

Introduction

The history of metabolic disorders has been traced to the addition of prenatal lifestyle manipulations and nutritional insults.1 The concept of fetal developmental programming and metabolic disorders is not entirely new; however, it has sustained consistent interest regarding the role of the gestational environment in fetal and neonatal development and growth.2 Fetal developmental programming posits that the fetal environment during development plays a crucial role in determining the risk of disease later in life. There is ample evidence in the literature describing a significant relationship between optimal in-utero nutritional exposure and postnatal development, including an elevated risk of disease following maternal environmental insults.3

Currently, there are numerous discussions about alternative therapies that may have few or no side effects and remain cost-effective for all. Although the mechanisms of action of these alternative medicines have yet to be experimentally elucidated, developing nations use them as alternative remedies.4 (AI) is a common name for , a plant frequently used in traditional African therapies for various ailments. It is a medicinal herb that originated in India and is now cultivated in almost every country in the world, including the USA. Some plants possess important multifunctional qualities derived from their specific bioactive components.4 It is a tropical evergreen tree native to the Indo-Pak subcontinent and is now found thriving in over 70 countries worldwide, virtually on every continent.5 Various biologically active compounds are isolated from different parts of the plant, and derivatives such as miliacin contribute to the bitter principles of its leaves.6 These compounds belong to a class of natural products called triterpenoids. They are slightly hydrophilic and completely lipophilic, with high solubility in solvents,7 and various parts of the tree have medicinal importance.8 The leaf has been reported to display a range of medicinal activities, and numerous properties have been documented without any reported side effects.9

In addition to their traditional importance, other reports on the medicinal effects of , based on scientific investigations, are readily available.10,11,12,13,14,15 The hypoglycemic effect of seed oil and leaf extracts has been reported in diabetic animal models.10,11,12 Ethanolic extracts of leaves have been shown to possess anti-lipid peroxidation, anti-hyperglycemic, and anti-hyperlipidemic properties in rats.12 Dairy animals have also been investigated; it was reported that leaf caused a significant reduction in hematological parameters in chickens,13 with no significant difference in certain hematological parameters following the extract's use in diabetic models.14,15

Despite the above evidence, there is a paucity of information on the role of in-utero neem leaf supplementation and its influence on hepatic function, lipid metabolism, and oxidative balance in the offspring of Wistar rats. This study evaluated the impact of dried leaf meal (DLM) of AI on indices of lipid homeostasis, including cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein, hepatic lipase, and lipoprotein lipase. The study also explored the impact of DLM on oxidative status and hepatic functions, as well as whether these effects are sex-dependent. The study was conceived to test the hypothesis that offspring exposed to DLM of AI would exhibit improved liver function, lipid homeostasis, and oxidative balance later in life.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

As stated in our previous study16, eighteen female Wistar rats weighing between 140 and 180 grams were used for this study. They were housed in cages with a 12-hour light/dark lighting condition. The rats had access to tap water and quality food and were acclimatized for one week. The experimental protocols were as outlined in our previous studies16.

Neem leaf () AI collection

Freshly plucked AI leaves from the tree in the village of Afowowa in Ewekoro Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria, were identified at the Biology Unit of D.S. Adegbenro ICT Polytechnic, Ogun State, Nigeria. The identified sample was deposited in the herbarium of the institution. The leaves were air-dried and ground with a blender to obtain the powdered form. Ethical approval for this investigation was sought and granted by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee.

Composition of Experimental Diet

About 500 grams of powdered AI leaves were pelletized with 25 kg of standard rat chow, which constituted the AI dried leaf meal (DLM), alongside a separate 25 kg of normal rat chow serving as the control (CONT) diet. The DLM was analyzed for protein, moisture, ash, fat, fiber, and nitrogen-free extract.11 (

Mating and Grouping

Female Wistar rats were mated with their male counterparts overnight16 and grouped as follows, with 6 animals per group:

Group A: Control male (CM) (treated with CONT diet throughout the experiment).

Group B: Control female (CF) (treated with CONT diet throughout the experiment).

Group C: Treated male (TM) (treated with dried leaf meal only during gestation).

Group D: Treated female (TF) (treated with dried leaf meal only during gestation).

All the pups, except those in the CM and CF groups, were transferred to the CONT diet until the end of the investigation at postnatal day (PND) 70. The offspring were reduced to 8 to 10 per litter on PND 1 (birth, day 0), weaned on day 21 postnatally, and housed in groups of three or four male and female pups per cage separately.

Isolation of Tissue

This was done as previously reported in our investigation16.

Blood sample

As previously reported by16, about four (4ml) of blood sample was gotten via cardiac puncture into plain bottles, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 minutes and the serum was carefully separated in to a clean Eppendorf bottle. The samples were stored at -20 ◦C until the period of analyses.18

Oxidative stress study

All parameters of oxidative stress were determined thus; superoxide dismutase and reduced glutathione,20 catalases and malonaldehyde.21

Liver function

Albumin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alkaline amino transferase (ALT) and aspartate amino transferase (AST) were investigated from the stored serum samples with the aid of an automated analyzer (Mindray BS-120, Chema Diagnostica, Italy).

Lipid profile

Automated analyzer was used to assay CHOL, HDL, LDL and TG levels from the liver homogenate samples ().

Quantification of Castelli indices

Castelli indices (CI) I, II, were quantified thus;

Total CHL

Castelli index I = HDL

LDL

Castelli index I = HDL.16

Hepatic lipase (HL) and Lipoprotein lipase (LPL)

Hepatic lipase (HL) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity was determined in liver tissue homogenate according to the previously described mehod17.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as previously described by16.

Results

Proximate composition of dried AI leaf

Percentage (%) proximate composition of the AI leaf and the constituents include; moisture (12.36), fat (2.21), crude protein (15.84), carbohydrates (51.63), crude fibre (13.13) and ash (4.83). (

Proximate composition of dried AI leaf

| Feed contents | (%) |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 12.36 |

| Fat | 2.21 |

| Crude protein | 15.84 |

| Carbohydrates (CHO) | 51.63 |

| Crude Fibre | 13.13 |

| Ash | 4.83 |

Vitamins Analysis of dried AI leaf

Results presented in

Vitamins Analysis of dried AI leaf

| Vitamins | Values |

|---|---|

| A | 1.864(mg/100g) |

| B1 | 0.312(mg/100g) |

| B2 | 0.343(mg/100g) |

| B6 | 35.611(mg/100g) |

| B9 | 2.864(mg/100g) |

| C | 308.542(mg/100g) |

| D | 1.681(mg/100g) |

| E | 3.289(mg/100g) |

Composition of Mineral elements in dried AI leaf

Results presented in

Mineral Compositions of dried AI leaf

| SN | Minerals | Values |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Sodium (Na)’ | 1389.167 mg/100g | |

| ‘Potassium (K)’ | 1216.738 mg/100g | |

| ‘Calcium(Ca)’ | 1569.712 mg/100g | |

| ‘Magnesium’ | 1096.443 mg/100g | |

| Zinc(Zn) | 4.386 mg/100g | |

| Potassium(P) | 628.136 mg/100g | |

| Iron(Fe) | 3.412 mg/100g | |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.121 mg/100g |

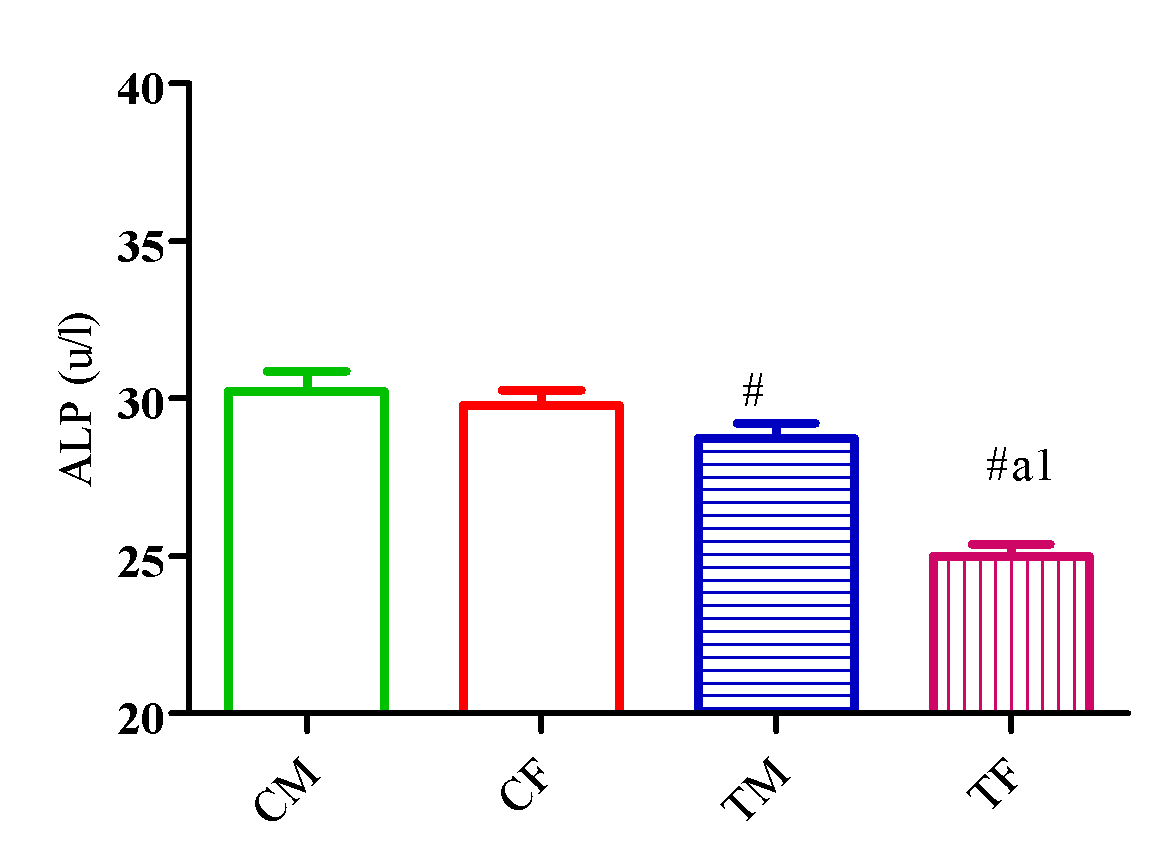

Outcome of DLM of A. Indica on markers of hepatic function (AST, ALT, and ALP)

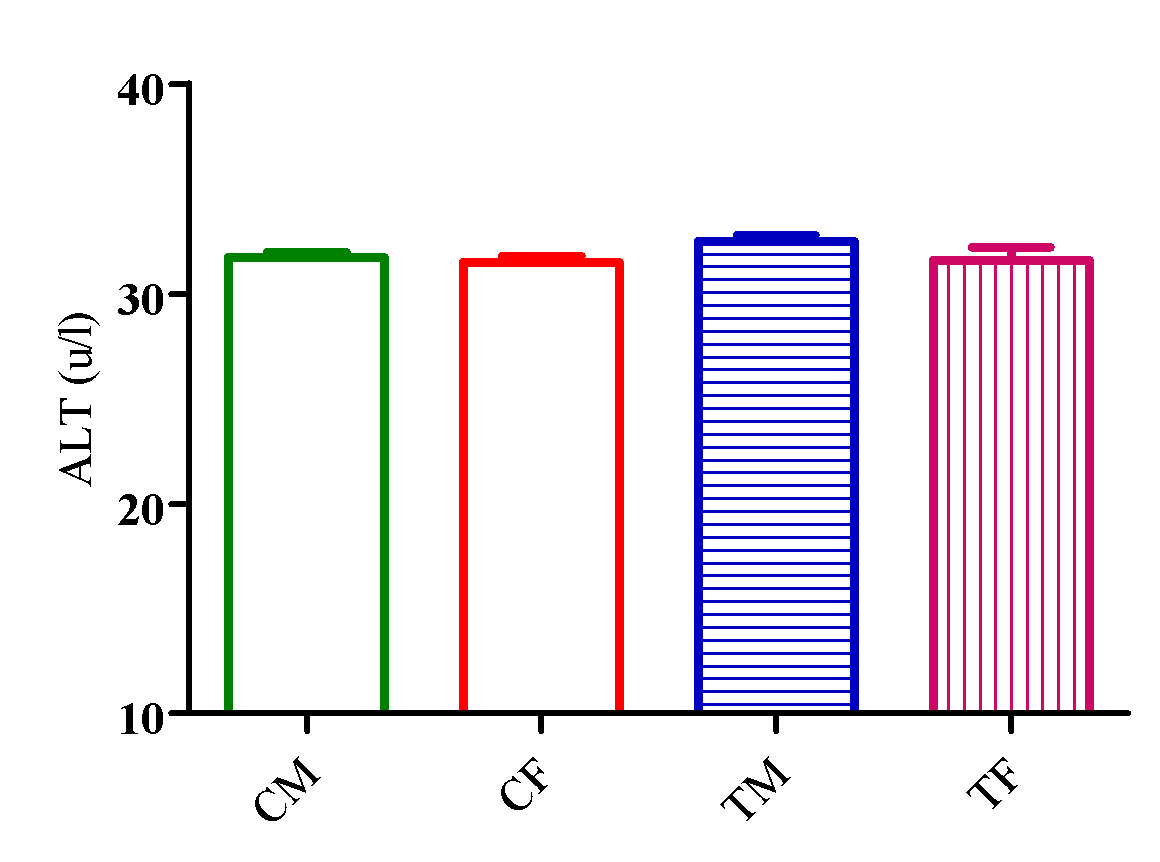

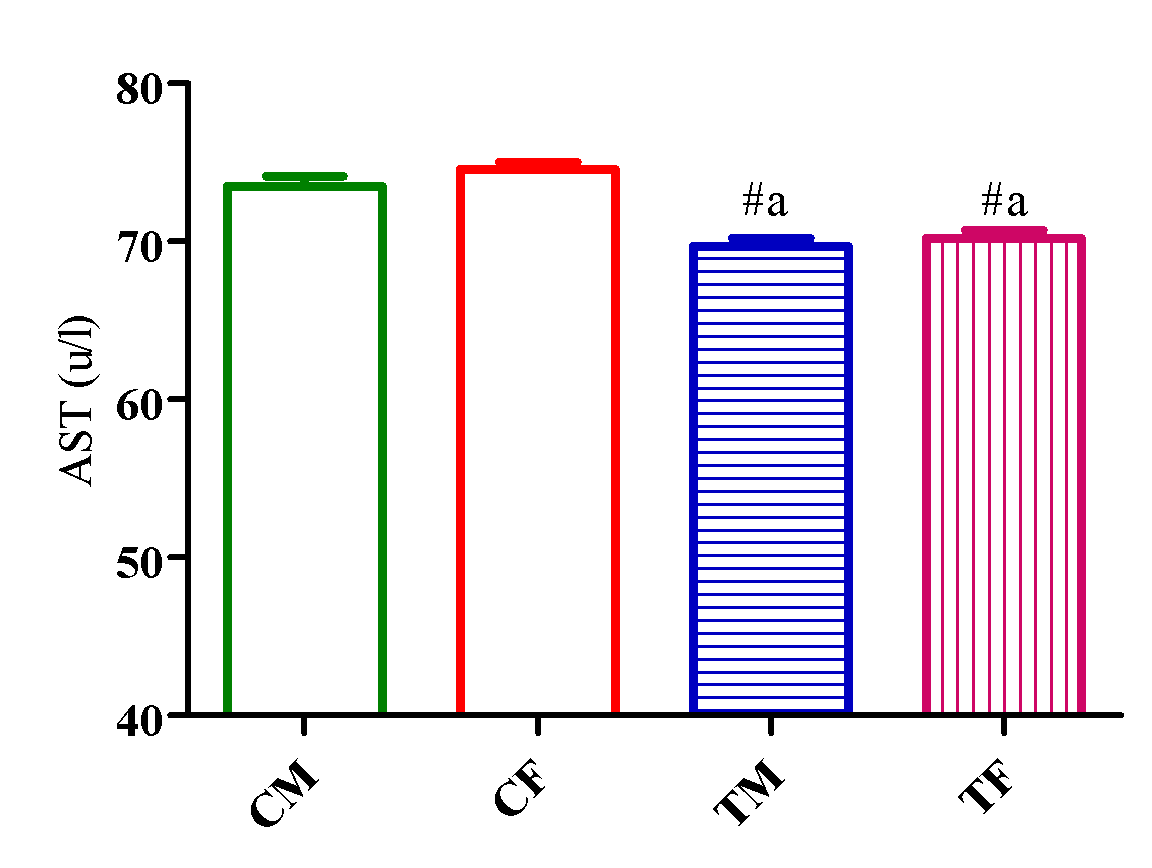

Figure 1 showed a significant reduction (p<0.05) in AST level in TM and TF compared with CM and CF with no significant difference (p>0.05) in ALT level in TM and TF compared with CM and CF (Figure 2).

However, AST level significantly decreased (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CM and CF with a significant elevation (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF (Figure 3).

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

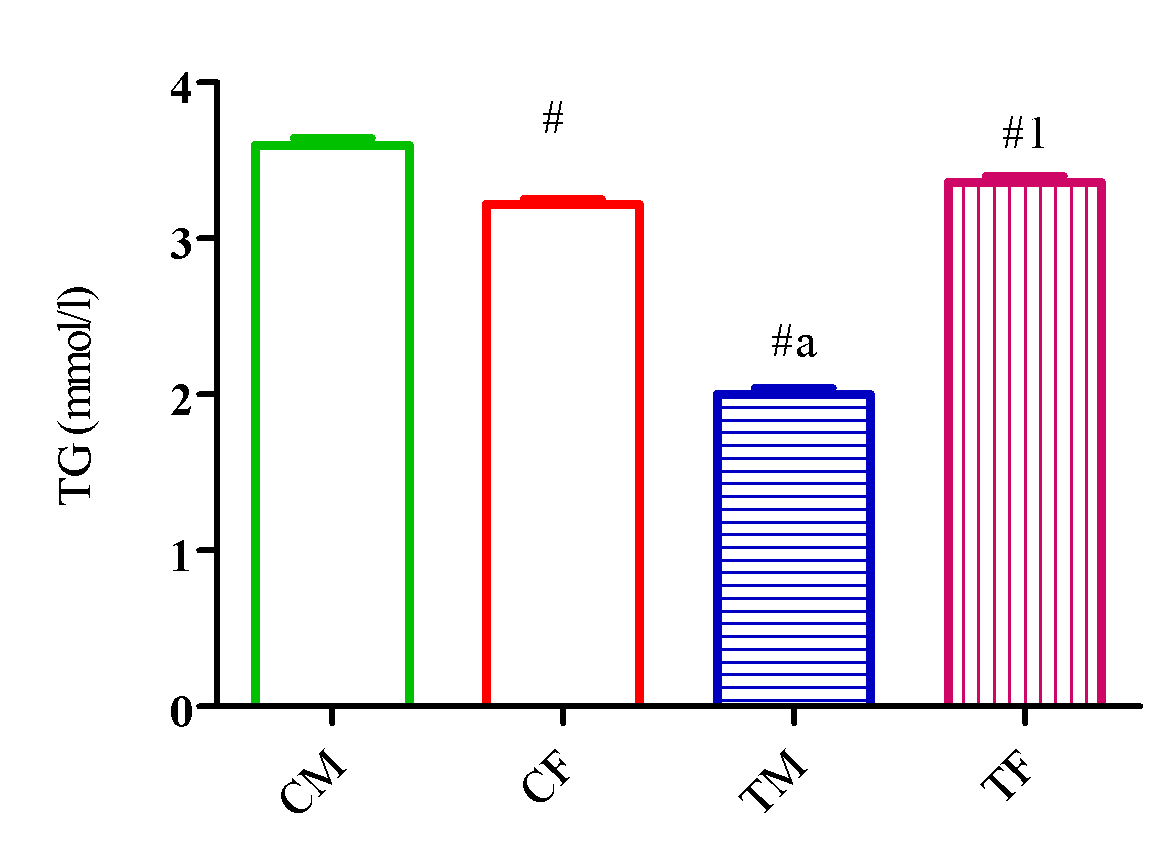

Outcome of DLM of A. Indica on indices of lipid homeostasis

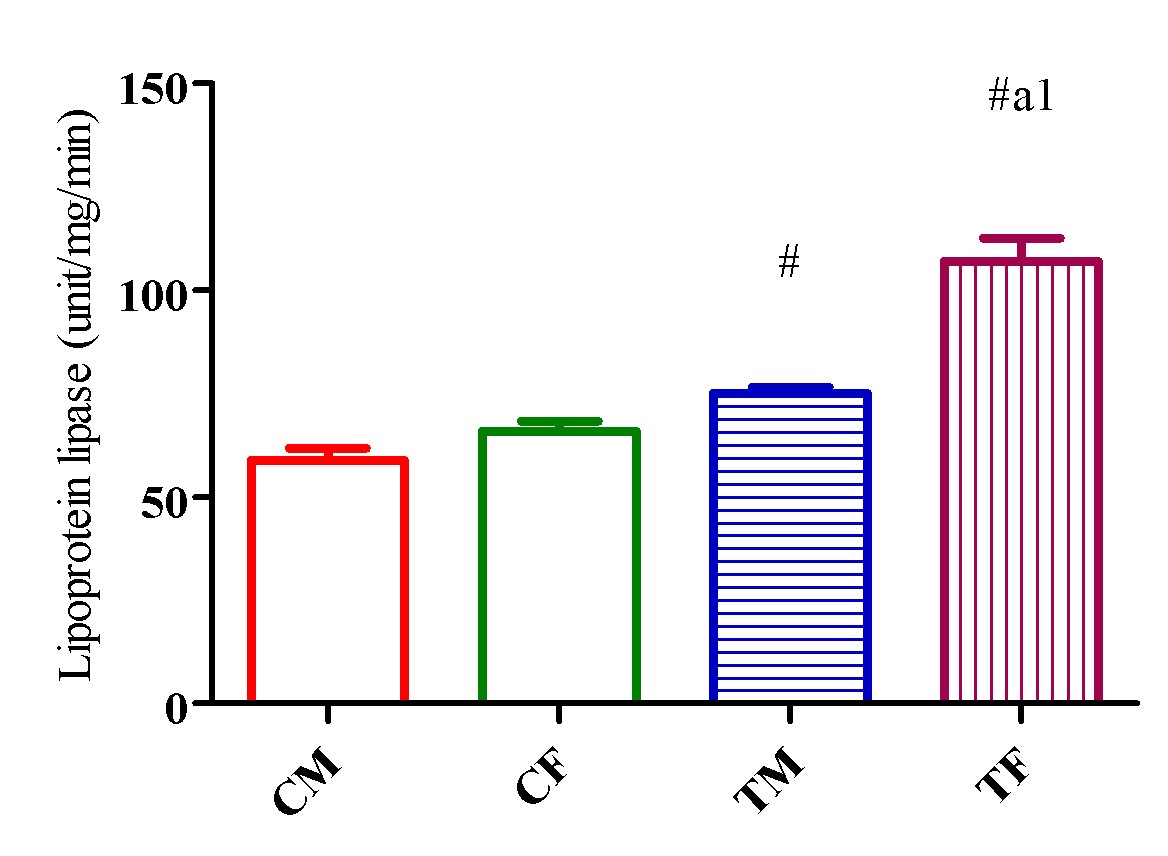

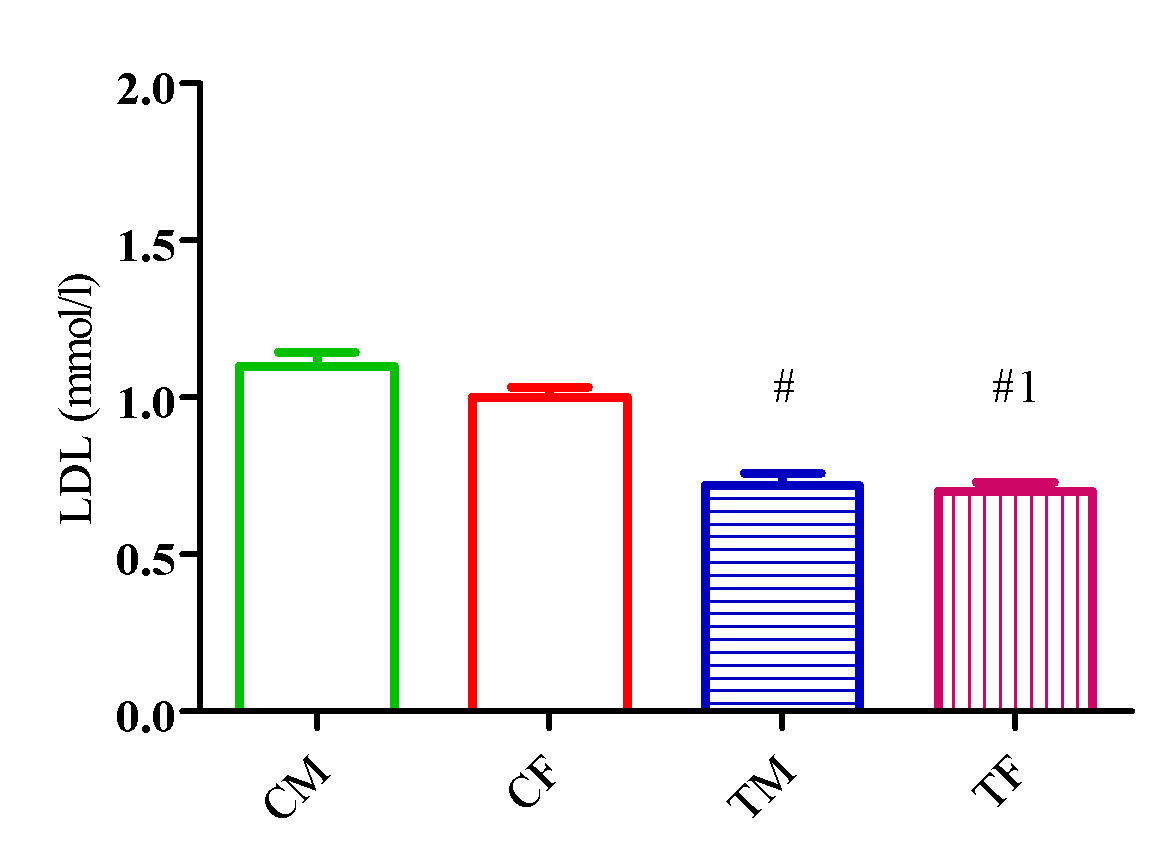

Figure 4 showed a significant reduction (p<0.05) in CHOL level in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TG level in TM and TF compared with CM. Also, TG level significantly increased (p<0.05) in TF compared with CF and TM (Figure 5).

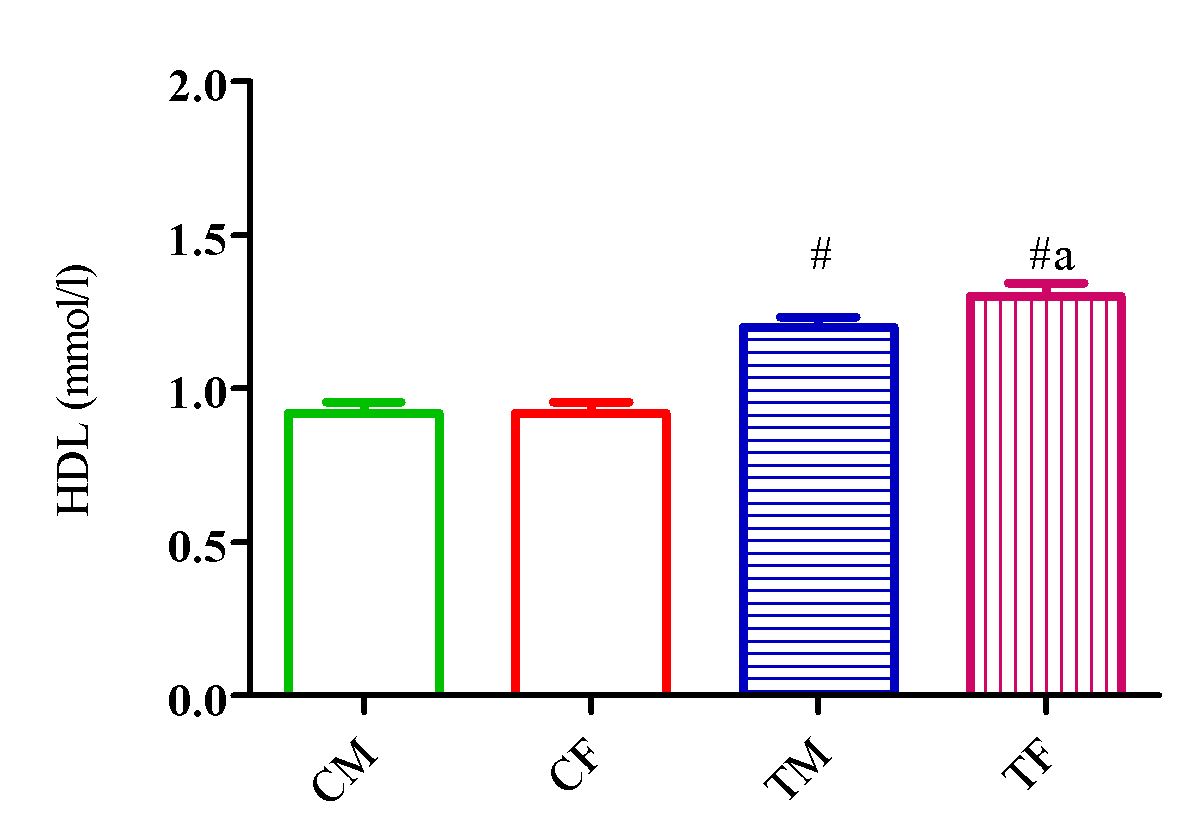

Figure 6 showed a significant elevation (p<0.05) in HDL level in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF.

Figure 7 showed a significant elevation (p<0.05) in LDL level in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF.

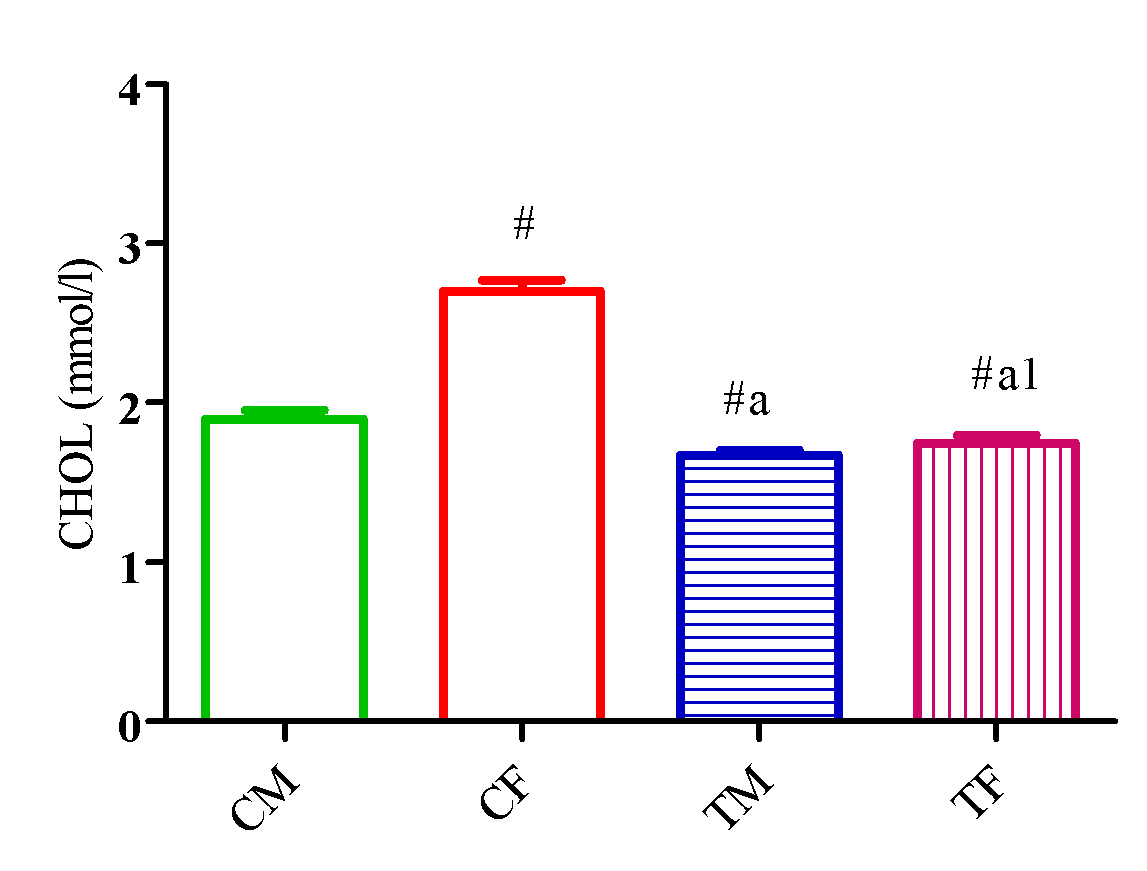

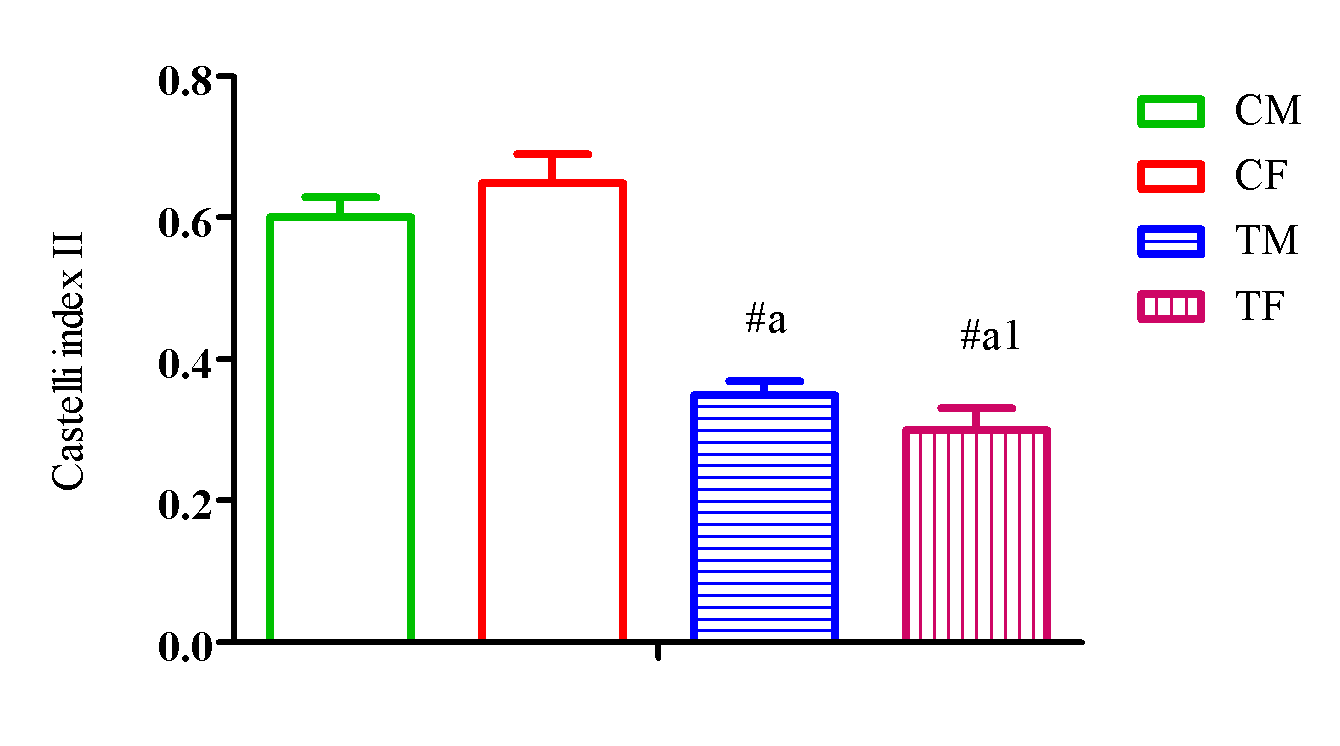

Figure 8 showed a significant elevation (p<0.05) in Castelli index I in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF.

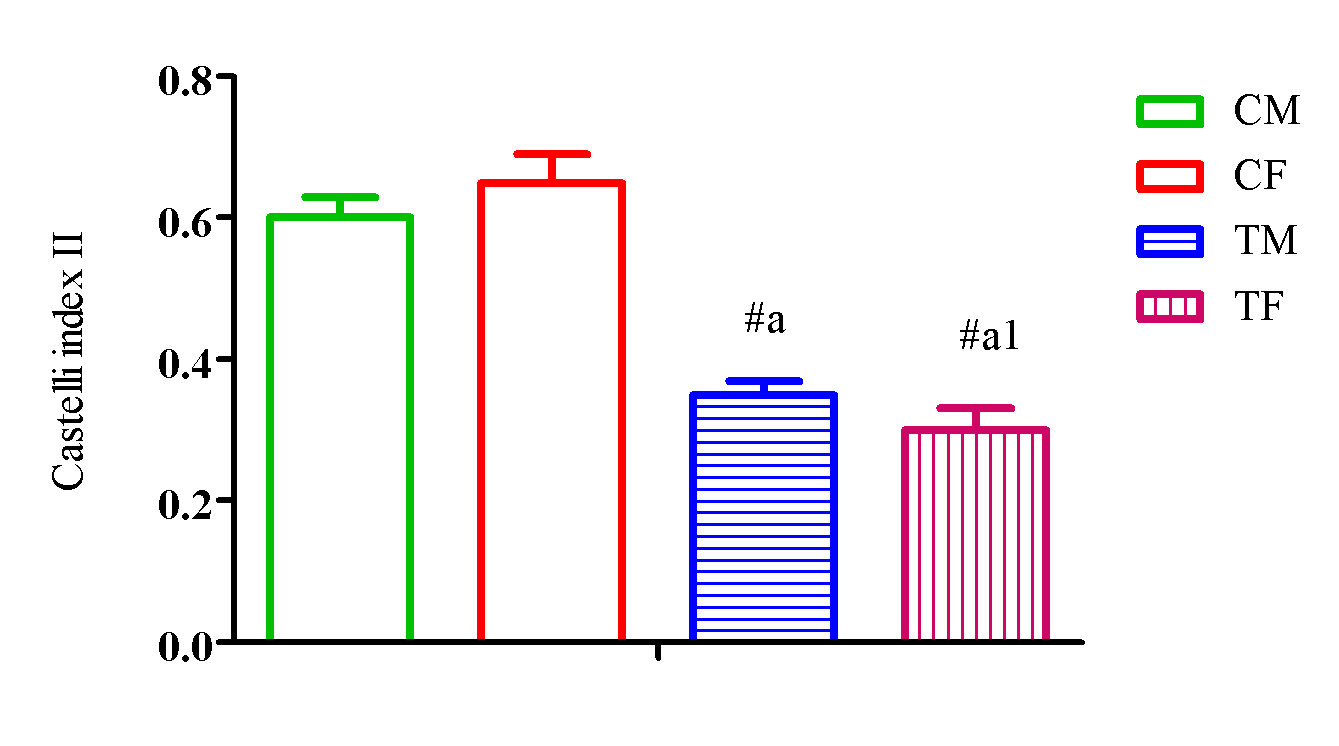

Figure 9 showed a significant elevation (p<0.05) in Castelli index II in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF

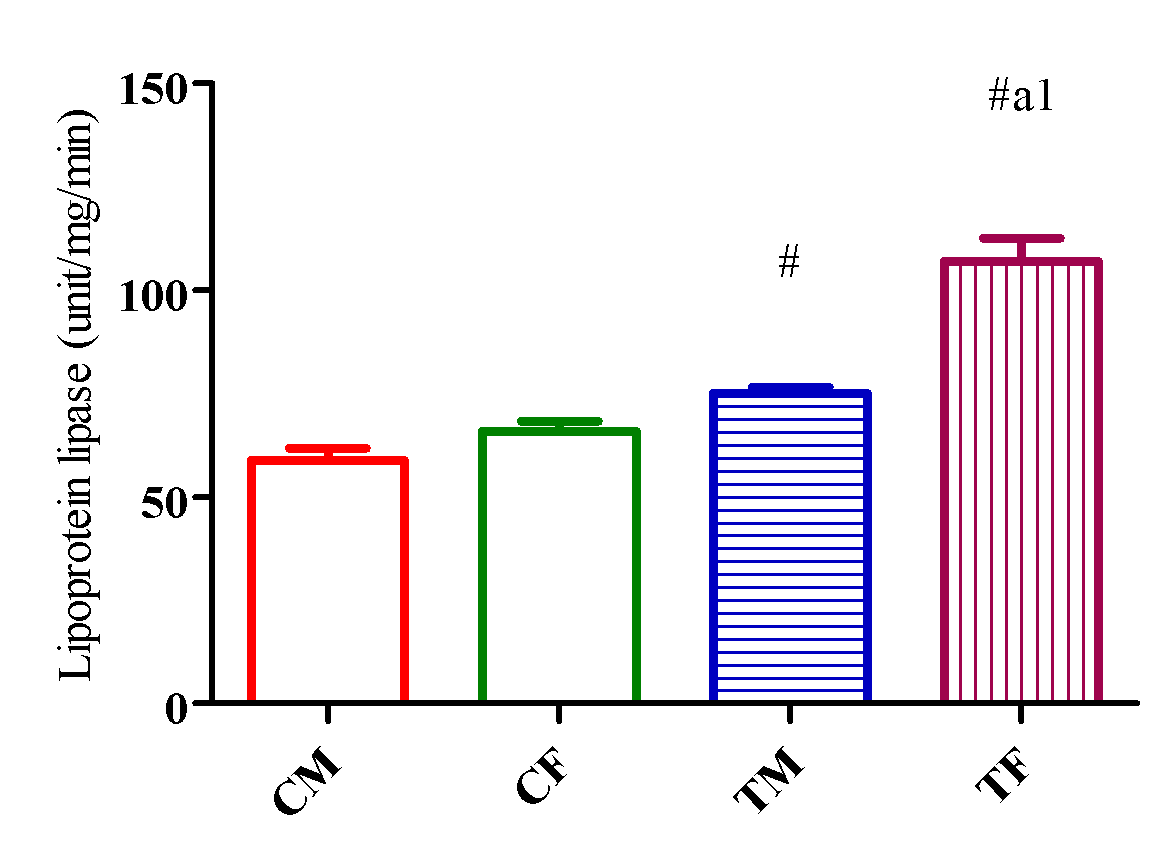

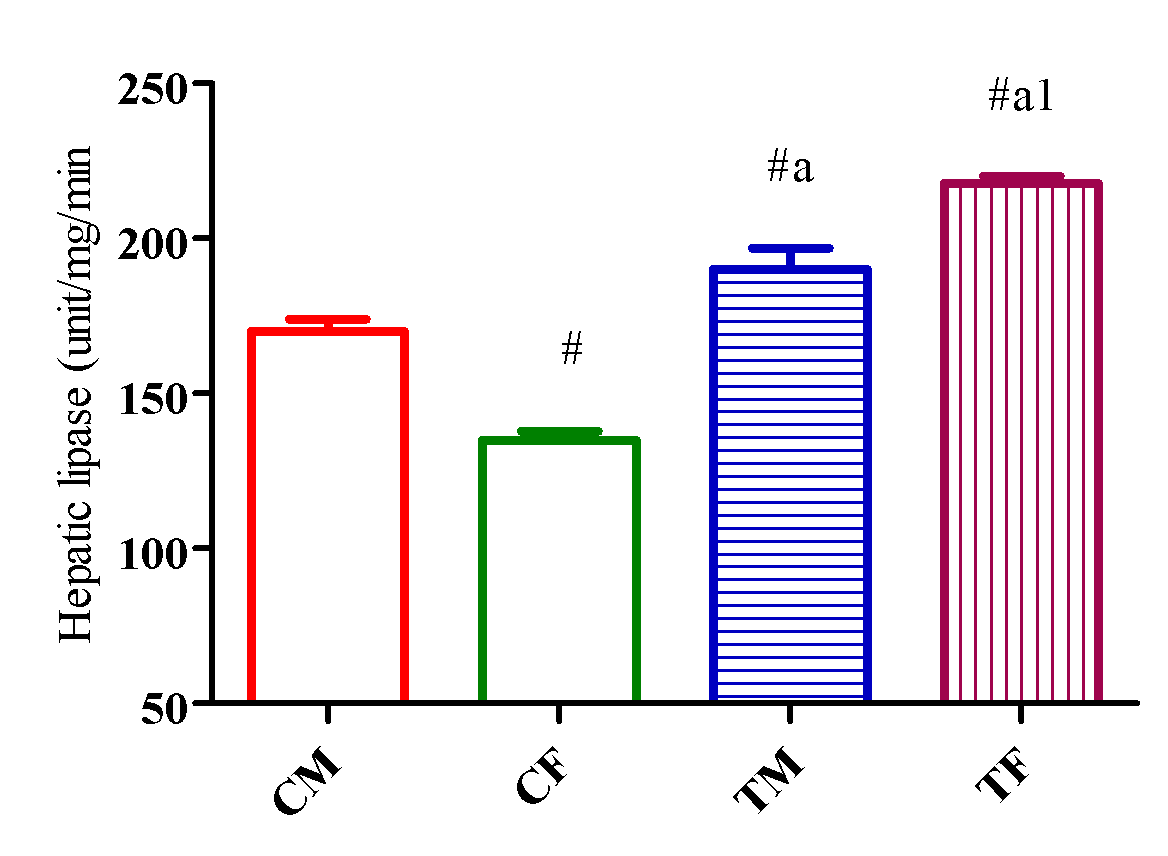

HL activity upregulated (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and downregulated (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF (Figure 10) while LPL activity significantly increased (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and downregulated (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF (Figure 11).

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

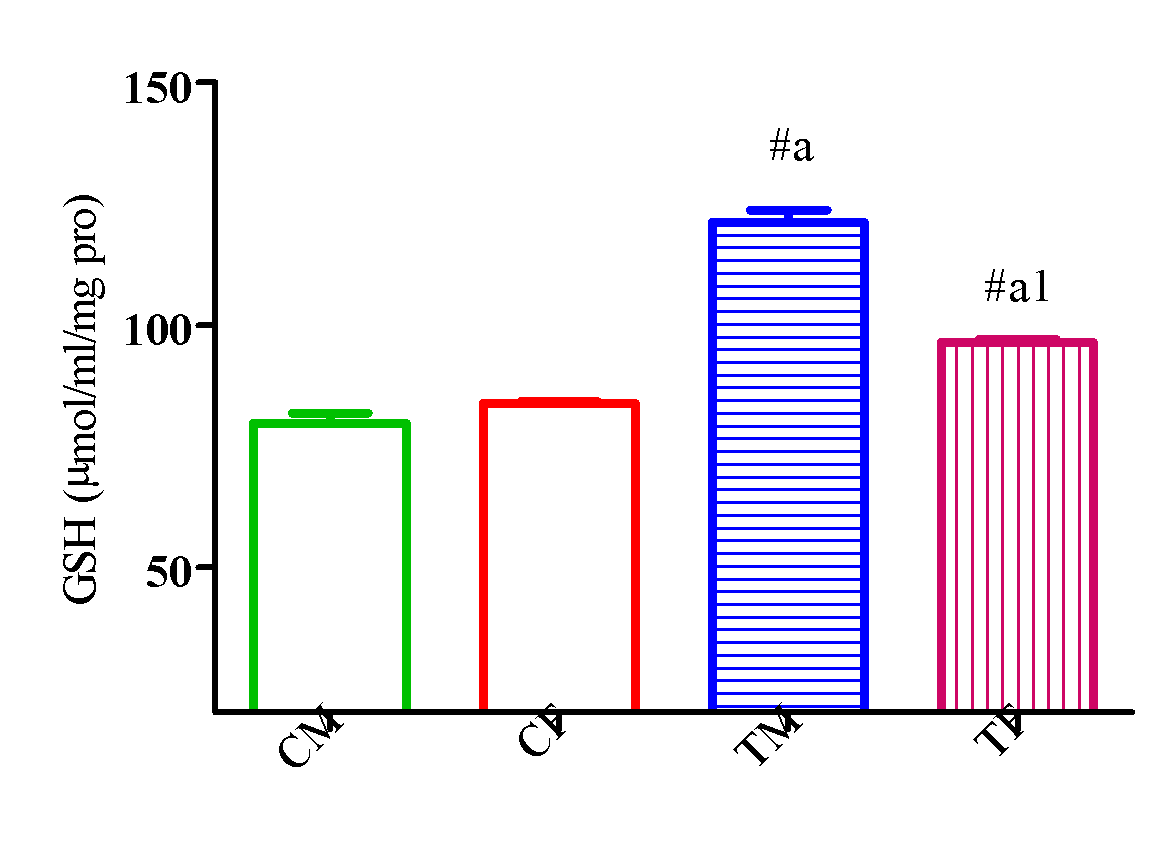

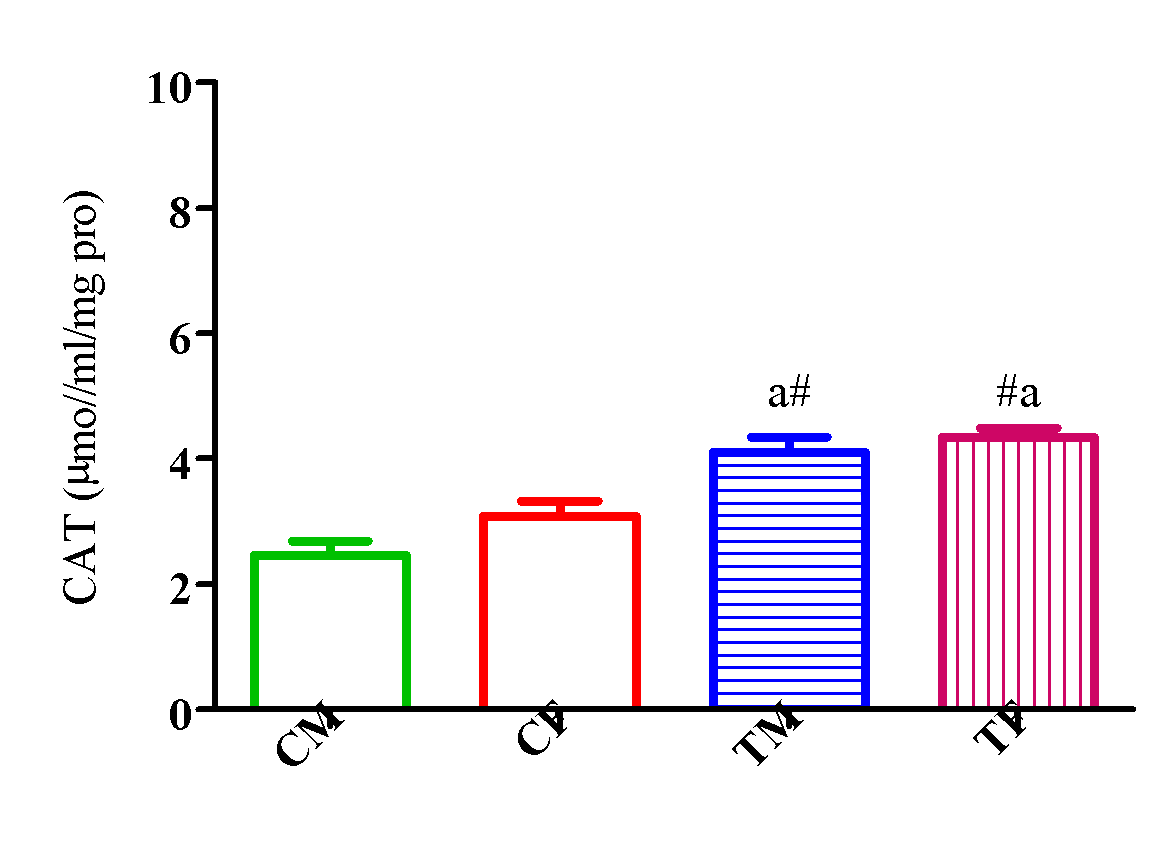

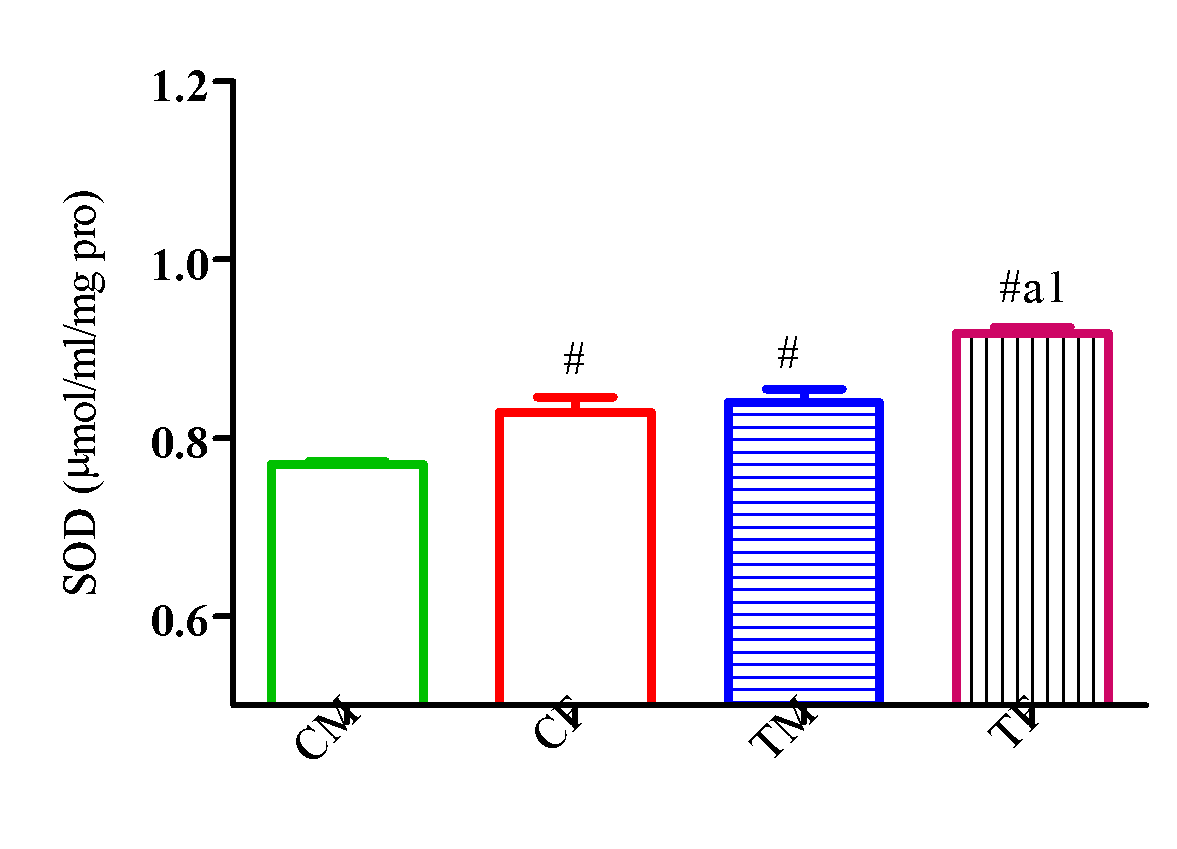

Outcome of DLM of A. Indica on markers of oxidative stress (GSH, SOD and CAT)

Figure 12 showed a significant elevation (p<0.05) in GSH activity in TM and TF compared with CM and CF and a significant elevation (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF.

Also, SOD activity significantly increased (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CM and CF with a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF (Figure 13).

The activity of CAT significantly increased (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CM and CF with a significant reduction (p<0.05) in TM compared with TF (Figure 14).

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

Outcome of DLM of

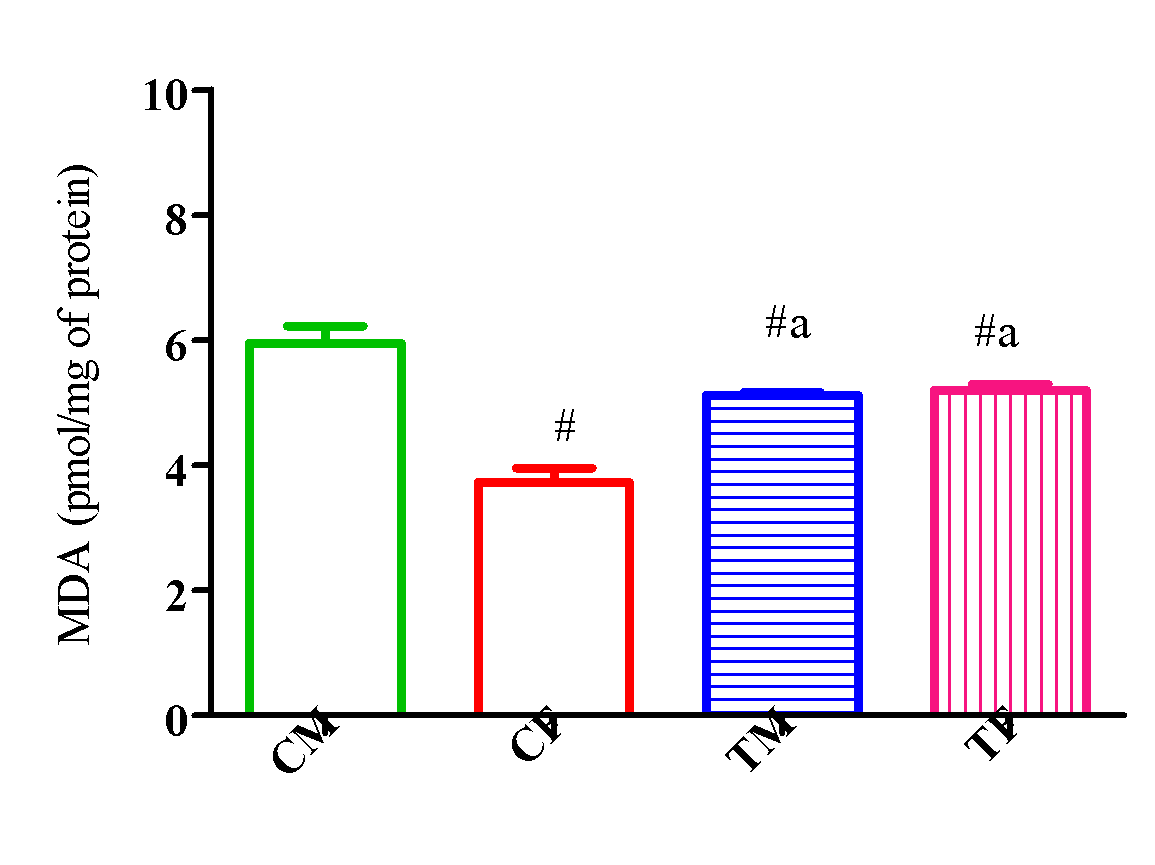

Outcome of DLM of A. Indica on lipid peroxidation’s index (MDA)

Figure 15 showed a significant reduction (p<0.05) in MDA activity in TM and TF compared with CM and a significant elevation (p<0.05) in TM and TF compared with CF.

Outcome of DLM of

Discussion

is one of the plants reported to possess chemoprotective potential and highly effective antioxidant effects.22,23 Its components contain compounds with impressive therapeutic applications,22 and several active compounds in the neem plant have been investigated as reported.24,25 Results from the present investigation revealed hepatoprotective effects in rat offspring exposed to dried leaf meal, as the markers of liver function assayed were significantly reduced. This is in agreement with a previous study that confirmed the non-toxic effect of neem leaf extract at varying doses on the liver.26

Interestingly, there was a reduction in the serum levels of TG, cholesterol, and LDL, and an elevation in HDL in offspring of rats exposed to dried leaf meal. The mechanism by which dried leaf meal induces a reduction in lipid parameters in this study could be explained by the stimulation of lipolysis27 and fatty acid utilization,28,29 and/or suppression of hepatic fatty acid synthesis in rodents. Serum cholesterol level was seen to be reduced progressively with increasing dietary levels of dried leaf meal in rat offspring. This conspicuous effect probably suggests a total reduction in the mobilization of lipid, though it is also possible that dried leaf meal might elicit an indirect inhibitory effect on HMG-CoA reductase, an important enzyme in the biosynthesis of cholesterol metabolism.

There was a decreased triglyceride level in offspring of rats exposed to dried leaf meal, which is suggestive of the hypotriglyceridemic effect of neem leaf. Furthermore, hepatic lipase is an enzyme that has been extensively investigated and is responsible for converting triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. Acetyl CoA is produced when free fatty acids are broken down in the hepatic tissue, and the heightened scale of acetyl CoA leads to cholesterol, triglyceride, and ketone bodies as a result of ketosis in the liver. An increase in the flow of free fatty acids promotes the production of very low density lipoprotein particles, which in turn are transformed into low density lipoprotein.30 Hence, increased hepatic lipase activity in this study may not be unconnected with decreased triglyceride levels observed in offspring of rats exposed to perinatal neem leaf supplementation.

Results from the antioxidant assay showed increased oxidative balance as evidenced by the increased activities of markers such as SOD, GSH, and CAT, with a concomitant decrease in the lipid peroxidation index of MDA. The free radical oxidation of lipid molecules starts from the fatty acylmethylene group adjacent to a double bond to form lipid hydroperoxides, which are capable of further reactions to yield various classes of peroxides.31

In this study, vitamin analysis revealed the presence of a high level of vitamin C, otherwise known as ascorbic acid, and quercetin, nimbosterol, carotenes, and ascorbic acid are compounds present in fresh, mature leaves of .32 Thus, the prevention of lipid peroxidation by the dried leaf meal could be attributed to the antioxidant activities of the flavonoids, carotenes, and ascorbic acid present in the leaves. This study further revealed that DLM of leaves demonstrated anti-lipid peroxidation, anti-hyperlipidemic, and hypotriglyceridemic activities, therefore justifying the potential of employing the leaf in the management of metabolic disorders.

Previous studies revealed the presence of some important compounds from A. indica leaf such as Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside, Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, Kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucoside, and Quercetin-3-O-L-rhamnoside,33 and it is presumed that these compounds may be responsible for its anti-hyperlipidemic activity, either wholly or partially.

Conclusion

It is therefore inferred from our findings that the levels of total serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and MDA were lowered with A. indica dried leaf meal, while SOD, GSH, CAT, hepatic lipase, and high-density lipoprotein were increased. Moreover, its anti-hyperlipidemic effect may provide a protective mechanism against the development of atherosclerosis. Thus, supplementation with A. indica leaves may be employed to combat oxidative stress-related diseases, hyperlipidemia, as well as atherosclerosis, in view of its anti-hyperlipidemic activity, although it was observed that the effects were sex-dependent.

Authors’ declaration

We wish to declare no personal or financial conflict of interest .

Author contribution statement

YUSUFF DIMEJI IGBAYILOLA, AINA OLAWALE SAMSON, ATOYEBI KAYODE AND

ADEBAYO-GEGE GRACE IYABODE, OZEGBE QUEEN BISI, LAWAN J HAMIDU, SALAHUDEEN UMAR

OLAMILEKAN: ‘Designed and conceived the investigations; carried out the investigation; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed kits, equipment, tools for data analysis and wrote the manuscript’.

Funding statement

Authors did not receive any specific grant for this research from any funding agencies either the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Sunday Ogunowo of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital Main Laboratory for the technical support.