Identification of known and new variants of non-syndromic Retinitis pigmentosa in 5 families by whole exome sequencing method in Yazd province

- Department of Biology Research Center, Ashkezar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ashkezar, Yazd, Iran

- Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

- Mother and Newborn Health Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

- Stem Cell Biology Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Abstract

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a genetically diverse group of inherited eye disorders characterized by progressive night blindness, loss of peripheral vision (tunnel vision), and the presence of "bone spicule" pigmentation in the retina. These symptoms can cause substantial visual impairment and sometimes emerge in childhood. The disease displays high clinical and genetic heterogeneity. The primary purpose of this study was to identify genes and pathogenic variants contributing to non-syndromic RP in five Iranian families, using whole exome sequencing (WES). Exome sequencing is considered one of the most effective approaches for discovering new genes associated with heterogeneous conditions like RP. In this study, exome sequencing was performed on one affected individual (proband) from each of the five families, followed by data analysis to identify candidate variants. Next, co-segregation analysis for these candidate genes was conducted using Sanger sequencing on the probands and their family members, confirming the findings. For all families included in this study (at least two patients per family), WES successfully identified the disease-causing variant, achieving a 100% diagnostic yield. Four novel gene variants were reported: AHI1:c.3287dupG:p.G1096f, CDHR1:c.1842delA:p.A614AfsX40, CNGB1:c.G2575A:p.V859I, and CNGA1:c.A1487C:p.Q496P, each found in a different family. Sanger sequencing validated all four variants among family members, with affected individuals in each family exhibiting phenotypes corresponding to their identified variants. These results demonstrate that whole exome sequencing is a powerful tool for identifying pathogenic mutations in heterogeneous diseases like RP. Moreover, the findings can be applied in the future to identify carriers and help prevent the recurrence of RP in these families.

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most prevalent inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD) and represents the leading cause of progressive, inherited vision loss, marked by substantial phenotypic and genotypic diversity1. Globally, RP affects between 1 in 750 and 1 in 9,000 individuals2. The clinical features of RP stem from progressive degeneration of the retina, which eventually involves the macula and fovea. This process leads to a gradual decline in the ability to adapt to darkness, night blindness (nyctalopia), light sensitivity (photophobia), narrowing of the visual field (tunnel vision), and ultimately, severe or nearly complete blindness3,4. Typically, retinal deterioration begins during the teenage years, with the most advanced symptoms manifesting by the fourth decade of life. However, there are variants of RP with both earlier and later onset that have also been documented5.

RP can be inherited in several patterns, including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked forms6,7. It is further classified as non-syndromic (which accounts for 65% of all RP cases and presents solely with visual impairment) or syndromic, where vision loss is accompanied by additional clinical features8. The complexity of genotype-phenotype correlations in RP highlights the importance of precise diagnosis, effective treatment, and prevention strategies, which require comprehensive clinical evaluation alongside molecular genetic testing.

To date, 307 genes and loci associated with retinal diseases have been identified (RETnet website: https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/, last accessed December 30, 2020). Various approaches have been used to identify candidate genes and pathogenic mutations, such as linkage analysis in large extended families, followed by targeted sequencing techniques9. Among these, massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) has greatly accelerated gene discovery and mutation detection in RP, a disease characterized by high genetic heterogeneity10.

Populations with a high prevalence of consanguineous marriages, such as Iran—where the rate is approximately 40%11 —offer valuable opportunities to study the gene mutations underlying autosomal recessive RP (arRP). In this study, we sought to elucidate the genetic causes of arRP in five Iranian families by employing whole-exome sequencing (WES). Our results add to the understanding of genotype-phenotype relationships and the underlying pathophysiology of RP.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

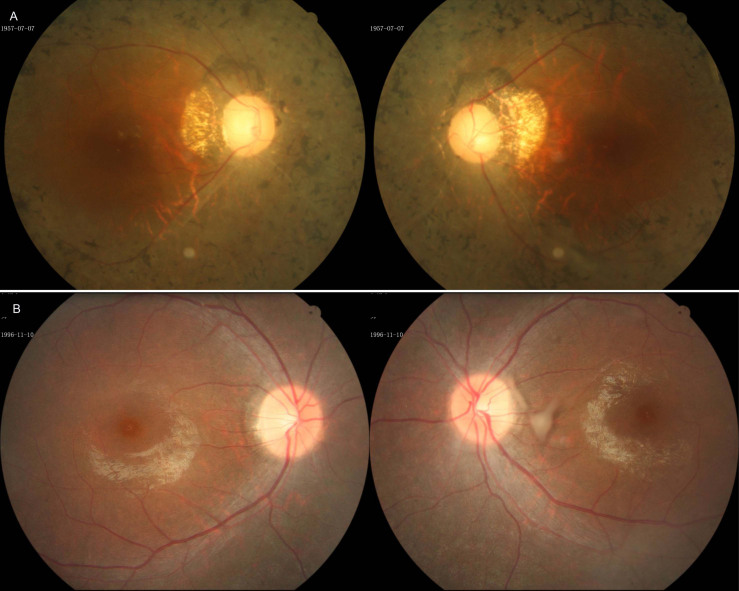

Based on a comprehensive pedigree analysis spanning at least four generations by a general practitioner, five Iranian families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (arRP) were selected for this study. Inclusion criteria required that each family have at least two siblings affected by non-syndromic RP, born to consanguineous parents. The diagnosis of RP was confirmed by expert ophthalmologists through medical records and thorough ophthalmic evaluations, which included, when appropriate, detailed fundoscopy, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), color vision testing, and slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to sampling. All study procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki12 and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR) in Tehran, Iran.

Molecular investigation

From each of the five families, one affected individual was selected for whole-exome sequencing (WES) and mutation screening. Genomic DNA was extracted from 5 ml of peripheral blood leukocytes from each participant and available family members (for co-segregation analysis) using the standard salting-out method13. Target regions were captured using the SureSelect Human All Exon kit (V6; Agilent Technologies Inc.), and each sample was barcoded. Every four samples were pooled and subjected to paired-end sequencing for 100 cycles on a single lane of the Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencing system (Illumina Whole-Genome Sequencing Service, Macrogen; Seoul, Korea).

Sequence reads from each exome were aligned to the human reference genome (hg38/GRCh38) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (V7.10)14. A sufficient sequencing depth (≥ 80) was maintained for reliable variant calling. Both single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) were identified with the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) version 3.3.015, and annotated using wANNOVAR16.

To filter the identified variants, only exonic and splicing variants were retained, while synonymous and non-frameshift variants were excluded. Given that all selected patients were from consanguineous marriages, the analysis focused on homozygous or compound heterozygous variants. Remaining variants with a minor allele frequency greater than 0.005 in databases such as the 1000 Genomes Project , NHLBI exome sequence data , ExAC , dbSNP , gnomAD , HEX , and HGMD were also excluded from further study.

To further refine the list of potentially pathogenic variants, additional filtering steps were employed. Variants present in ClinVar , the Iranian National Genome Database (Iranome; iranome.ir), and an in-house exome control dataset from 200 ethnically matched unaffected individuals were excluded. Following this, the biological functions of genes associated with the remaining variants were evaluated using databases such as OMIM , RETnet, PubMed , and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot . This step aimed to identify variants within genes linked to retinal diseases.

The selection criteria prioritized variants with a high likelihood of causing functional disruption—such as stop-gain, stop-loss, insertions, deletions, nonsense, and missense mutations with a GERP++ conservation score greater than +2 and a CADD score over 2017, as well as those affecting consensus splice sites. The functional impact of these mutations was then predicted using the dbNSFP database18, which integrates six algorithms including PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and MutationTaster. All candidate variants were classified based on the guidelines established by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMGG)19.

To validate the identified mutations and assess their segregation within families, primers for each candidate variant were designed using Primer3 (v. 0.4.0) software . PCR amplification was performed with the Taq DNA Polymerase Master Kit (ROJE Technologies, Iran) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing of the PCR products utilized the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI 3730XL Automated Capillary DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Resulting sequences were analyzed using CodonCode Aligner Software (V8.0.2). All primer sequences are available upon request.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

All families, of Persian origin, were recruited through the Fayazbakhsh state welfare organization in Yazd province, central Iran. Each proband underwent comprehensive ophthalmological evaluations, and detailed demographic and clinical data are summarized in

Summary of clinical symptoms of patient

| Family name | proband | age | Sex | nationality | consanguineous marriage | Number of affected | Clinical presentation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP100 | RP101 | 47 | male | Persian | Yes | 2 | Retinal disorder - reduced visual acuity - color blindness - night blindness | RP |

| RP200 | RP201 | 33 | woman | Persian | Yes | 2 | Retinal disorder - reduced visual acuity - color blindness - night blindness | RP |

| RP300 | RP301 | 66 | male | Persian | Yes | 3 | Retinal disorder - reduced visual acuity - color blindness - night blindness - cataracts | RP |

| RP400 | RP401 | 65 | woman | Persian | Yes | 3 | Retinal disorder - reduced visual acuity - color blindness - night blindness - cataracts | RP |

| RP500 | RP501 | 13 | male | Persian | Yes | 2 | Retinal disorder - reduced visual acuity - color blindness - night blindness - nystagmus - strabismus | RP |

Molecular Findings

Among the five index patients who underwent whole-exome sequencing, candidate disease-causing mutations were identified in four different known RP genes across four probands. All detected causal variants were homozygous and are detailed in

Consequently, exome data from four probands (RP100 to RP400) were analyzed to identify common population reference SNPs (rs) within a 4 Mbp region surrounding the CNGA1 gene. In the RP05 family, no new potentially pathogenic homozygous or compound heterozygous variants were detected in any known retinal disease genes. For this family, all other identified variants were re-evaluated using various databases; however, no homozygous or compound heterozygous variants were found. Sanger sequencing validated all four identified homozygous variants and confirmed complete co-segregation of these variants with the disease phenotype in the respective families.

Summary of clinical symptoms of patients

| Number | Gene | Variante | location | Mutation type | Associated diseases | Phenotypic correlation | Inheritance pattern | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP100 | AHI1 |

c.3287dupG p.G1096GfsX8 |

Chromosome 6 Exone 24 |

Frameshift dup - >G | RP | Yes | AR | new mutation |

| RP200 | CHDR1 |

c.1842delA p.A614fsX40 |

Chromosome 10 Exone 16 |

Frameshift deletion A > - | RP | Yes | AR | new mutation |

| RP300 | CNGB1 |

c.G2575A p.V859I |

Chromosome 6 Exone 26 |

Missense C > T | RP | Yes | AR | new mutation |

| RP400 | CNGA1 |

c.A1487C p.Q496P |

Chromosome 4 Exone 11 |

Missense T > G | RP | Yes | AR | new mutation |

| RP500 | AIPL1 |

c.G834A p.W278X |

Chromosome 17 Exone 6 |

Missense C > T | RP | Yes | AR | known mutation |

Discussion

Progressive decline in rod photoreceptor function, followed by irreversible loss of cone photoreceptors, underlies retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a leading cause of legal blindness. In this study, we present the molecular and clinical findings from five Iranian families, all of whom meet the diagnostic criteria for autosomal recessive RP (arRP). Notably, the same mutation in the CNGA1 gene (NM_000087; c.A1475C; p.Q492P) was found to co-segregate with the RP phenotype in two unrelated consanguineous families, RP01 and RP05, both of which involved first-cousin and third-cousin marriages, respectively. This mutation, previously unreported and predicted as likely pathogenic according to ACMG guidelines, resulted in strikingly similar clinical features among affected individuals in both families. RP01 originated from Tabas and RP05 from a remote village in Taft—two cities in Yazd province about 400 kilometers apart—without any known consanguinity between the families in previous generations. This geographic spread and shared mutation suggest the presence of a founder variant inherited from a common ancestor in the Yazd population. To test this hypothesis, exome data from two probands (RP011 and RP051) were analyzed for shared population-specific variants in a 4 Mbp region containing CNGA1. As shown in Figure 2 (Supplement), both families shared a similar 1.5 Mbp ancestral haplotype block in the mutation-bearing region, supporting the founder effect theory. Further confirmation by Sanger sequencing of these variants in case and control groups will be needed to validate this finding. Identifying founder mutations common to specific regions or ethnicities enhances genetic testing for diagnosis and carrier screening by increasing sensitivity, specificity, throughput, and cost-effectiveness.

The CNGA1 gene, primarily expressed in rod photoreceptors, encodes the α subunit of the rod cGMP-gated channel (CNG), which plays a crucial role in the final step of the visual phototransduction pathway20. Mutations in CNGA1 can cause RP49, a subtype of arRP characterized by classic RP features21. The clinical presentation of our patients was consistent with these typical characteristics. Interestingly, the frequency of RP patients with CNGA1 mutations is higher in Asian populations than in Europeans22,23, with c.265delC and c.1537>A described as founder variants in South Asia22.

In family RP02, four children of an asymptomatic first-cousin couple were found to carry a splicing mutation in RPGRIP1 (NM_020366; c.2710+1G>T), not previously described but predicted to be deleterious and pathogenic, and segregating with the disease. Previously, a homozygous novel c.2889delT (p.P963fs) mutation in this gene was reported in Iranian patients with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA)24. Other studies in 50 Iranian cohorts with inherited retinal diseases (IRD) identified the same gene mutation (NM_020366; c.1306G>T; p.Ala436Ser) causing LCA in two unrelated patients and cone-rod dystrophy (CRD) in one patient25. Approximately 5% of LCA cases are attributed to biallelic pathogenic RPGRIP1 variants26. However, the frequency of these mutations varies by ethnicity: 8.8% in Japanese and 7.6% in Chinese cases27,28, but not among the top three mutated genes in European29, Brazilian30, or Australian31 LCA patients. RPGRIP1 mutations can also cause juvenile RP32. The RP02 patients exhibited some LCA features, such as severe visual disturbance in infancy and nystagmus, but lacked the Franceschetti oculo-digital sign characteristic of LCA, highlighting the phenotypic variability often seen in this disorder.

RPGRIP1, a scaffolding protein, is involved in multiple biological functions, including retinal development, nuclear localization, neural precursor cell proliferation, and disc morphogenesis by anchoring RPGR to the connecting cilium. This connection links the inner and outer segments of photoreceptors, supporting ciliary function and outer segment morphogenesis33.

A previously reported splicing-site mutation in the PDE6B gene (Exon 15; NM_000283; c.1920+2T>G) was identified in the RP03 family. This family included seven affected individuals—four children of first-cousin healthy parents (RP031-34), and three offspring of a first cousin once removed couple (RP035-37) (Figure 1 (Supplement)). This mutation, previously reported in a Japanese population34, further supports its pathogenicity. Two other novel mutations in PDE6B (a splicing-site mutation in Exon 8, NM_000283; c.1060-1G>T35 and a deletion in Exon 5, NM_000283; c.782_784del; p.Phe261del25) have also been reported in the Iranian population with non-syndromic arRP. Mutations in PDE6B, which encodes the β subunit of the rod photoreceptor cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase (PDE), are implicated in several visual impairment disorders36. Among non-syndromic arRP patients, PDE6B mutations account for 2–5% of cases (RP40; OMIM 180072)37. In the Pakistani population, mutations in PDE6A and PDE6B account for 2–3% of arRP cases38. In an Indian family, a homozygous missense mutation in PDE6B, along with mutations in BBS10 and AR, led to Bardet-Biedl syndrome in two siblings39, showing that PDE6B mutations can also cause syndromic RP. Rarely, heterozygous mutations in this gene may cause congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB) with dominant inheritance and varying severity40,41. Disruption of PDE6B function leads to increased cGMP and Ca2+ influx, causing rod photoreceptor apoptosis42. Mouse models (rd1 and rd10) with Pde6b mutations have been used in studies of treatment modalities, such as the Cas9/RecA system, with promising results43. Human clinical trials of gene augmentation strategies are also underway44. Clinically, patients with PDE6B mutations typically experience early-onset night blindness45,46,47, often diagnosed earlier than those with other RP variants47. In RP033, the proband from the RP03 family, the first ocular symptoms began at age 14, with diagnosis at 28—a pattern similar to previous reports from South Korea and France47,48. Early-onset cataract associated with PDE6B mutations has also been reported in Caucasian patients49.

In the RP04 family, no pathogenic variants were identified, suggesting that the causative mutation may lie in genes not yet linked to retinal dystrophy, noncoding regions (such as deep intronic or regulatory sequences not captured by WES), or less likely, in regions with suboptimal coverage. Review of exome data using integrative genome viewer (IGV) confirmed that all genes known to underlie retinal diseases were adequately captured, making it unlikely that a known mutation was missed. Other mechanisms, such as large genomic rearrangements undetectable by WES, may be responsible for unsolved cases.

Conclusion

In summary, uncovering the molecular basis of RP cases significantly advances clinical diagnosis, carrier screening, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis, long-term prognosis, patient management, family planning, and the development of emerging gene-based therapies to restore vision. However, the limited available evidence regarding phenotype-genotype correlations in RP presents ongoing challenges for identifying causative gene mutations. Our findings highlight the clinical value of whole-exome sequencing (WES) in establishing genotype-phenotype associations in non-syndromic arRP, thereby expanding current knowledge of these diseases. Furthermore, this study broadens the known mutational spectrum of CNGA1, PDE6B, and RPGRIP1, and reveals a founder variant in CNGA1 in central Iran. Future functional studies are needed to clarify the cellular and molecular effects of these variants and to enable definitive genetic diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the patients and relatives for participating in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the State Welfare Organization of Iran [USWR-1190].

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.