Influence of Social Media Usage, Academic Performance and Working Memory among Undergraduate Students

- Medical Department, School of Health Sciences, University of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia

- Department of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, Batumi State University, Batumi, Georgia

- Department of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, East European University, Tbilisi, Georgia

- Department of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia

Abstract

Social media has become a crucial tool for maintaining productivity among undergraduates, concomitant with a global increase in user numbers. This study evaluated the influence of social media use on undergraduates’ academic performance and working memory. Participants from three universities—the University of Georgia (UG), East European University (EEU), and Batumi State University (BSU)—completed an online questionnaire administered via Google Forms. UG and EEU are located in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, whereas BSU is located in Batumi. The study protocol, including the questionnaires, was approved by the respective institutional review boards before data collection. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were calculated using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Overall, 41.3% of respondents were male, and the majority were international students studying in Georgia. A total of 87.9% of participants reported being frequently dissatisfied because they wished to devote more time to social media. Social media use varied significantly according to participants’ age, sex, and geographic location. These findings demonstrate the growing prevalence of social media use and its potential impact on academic achievement and working memory among undergraduate students.

Background

The global use of social media and its regulation among students remains a significant public-health challenge. Social media use has been associated with increased productivity among undergraduates, coinciding with an expanding user base 1,2. Social-media platforms—websites or applications that students use to interact with peers 3, share ideas 4, and enhance social visibility 5—served multiple educational functions during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic 6, when social gatherings were restricted. Most students possess social-media accounts; for example, Facebook reports 2.9 billion monthly active users 7. Students find these platforms helpful for maintaining long-distance friendships and family relationships 8. Moreover, they can provide access to scholarships 9 and educational events 10,11. Systematically evaluating the advantages of Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Google+, Pinterest, and online forums is, however, time-consuming. Many students remain online for prolonged periods 12,13, thereby dedicating less time to study and potentially impairing preparation for quizzes, examinations, and overall academic performance 14. Empirical studies indicate that social-media exposure may modulate memory processes 15,16. Working memory is a critical cognitive resource for academic activities 17, enabling students to solve problems and comprehend instructional materials 18,19. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which social media influences working memory are not yet fully elucidated. Some investigations have reported beneficial effects 4,2021 that may facilitate educational and scientific activities and ultimately enhance academic performance 14. Despite these findings, only a minority of students employ social media primarily for educational purposes 22, and most studies have detected no significant association between overall social-media use and grade-point average (GPA) 5,23,24. Furthermore, few studies have examined social-media engagement in relation to students’ working memory. Although good academic performance does not necessarily imply optimal memory, academic failure is more frequent among students with memory impairments 25.

The present study therefore aimed to investigate the impact of social-media use on working memory and academic performance among undergraduates from three universities—two in Tbilisi and one in Batumi. We analysed the associations between social-media exposure, working-memory indices, and GPA. The resulting evidence is expected to inform students about the evolving influence of social media on their academic and professional development.

Methodology

Study Design

This cross-sectional observational study was designed to examine the influence of social media use on working memory among undergraduate students from three different universities in Georgia.

Data Collection

A total of 722 participants completed the study. An electronic survey was distributed to undergraduate students at the University of Georgia (UG), East European University (EEU) and Batumi State University (BSU) via Google Forms. UG and EEU are located in Tbilisi, whereas BSU is situated in Batumi. Data were collected between 14 June and 2 July 2023. To prevent duplicate submissions, respondents entered a university-specific code; all data were handled confidentially.

Participants

Eligible participants were male and female students aged ≥ 18 years, including both Georgian nationals and international students residing and studying in Georgia. No incentives were provided, and all responses were anonymous.

Informed Consent

Detailed information sheets and statements on data privacy accompanied the consent form, allowing each participant to review them before enrolment. Ethical approval was obtained from the Bioethics Council of the University of Georgia.

Evaluation Tools and Techniques

The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic data (e.g., age, sex, academic institution) and three sections: the Social Media Usage scale (SMU), the Academic Performance scale (APS), and the Working Memory questionnaire (WMQ).

The SMU scale was developed on the basis of the nine DSM-5 criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder; it consists of nine dichotomous (yes/no) items assessing social-media use on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Pinterest, TikTok, Google+, weblogs, and forums during the preceding year 26. Questions on preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal, persistence, displacement, problems, deception, escape, and conflict were included in the measure, all of which are elements of behavioral addiction 27,28,29,30,31. According to DSM-5, an individual who meets five or more of the nine criteria for at least 12 months is classified as having Internet addiction 26,27.

The APS contains eight items rated on a five-point Likert scale as follows: strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). Total scores are interpreted as excellent (33–40), good (25–32), moderate (17–24), poor (9–16), or failing (0–8).

The WMQ comprises 30 questions divided equally among the storage, attention, and executive domains 32. Each subcategory includes 10 randomly presented items: the storage domain assesses short-term storage capacity, text comprehension, and mental articulation; the attention domain addresses distraction and multitasking; and the executive domain evaluates planning and decision-making abilities. Each question is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 4 (severe problems in daily life) to 0 (no problem). The maximum score for each domain is 40, and the total score therefore ranges from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating greater complaint severity 33.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were calculated for all variables. Associations between social media use, academic performance, and working memory were examined, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Students scoring < 24 on the ALS scale and > 25 on the WM scale were classified as “needs improvement.” Odds ratios (ORs) and prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported.

Results

Students’ demographic distribution

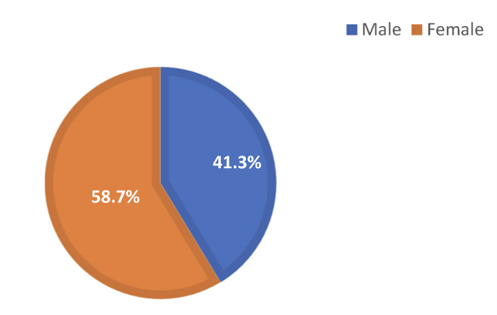

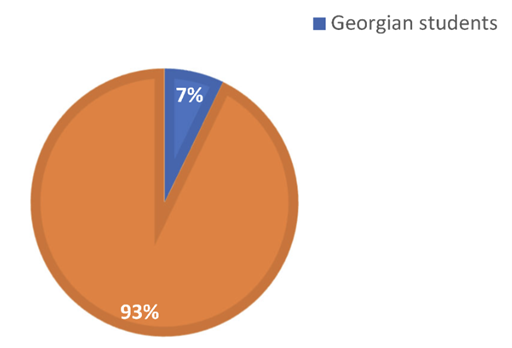

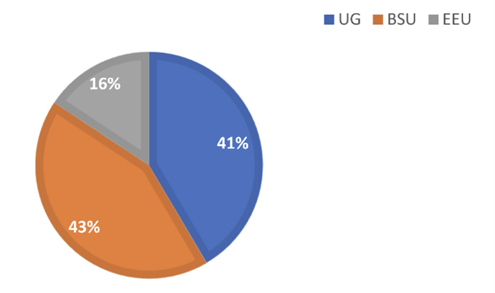

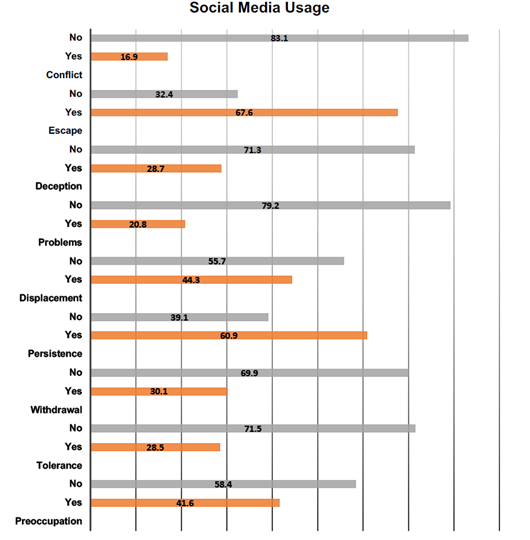

Among the participants, 58.7 % were female (Fig. 1.0); the mean (± SD) age was 21.94 ± 2.8 years, and the majority were international students (Fig. 2.0) from all three universities (BSU, UG, and EEU; Fig. 3.0). Figure 4 demonstrates that the prevalence of social media usage disorder was higher in the categories of pre-occupation (41.6 %), persistence (60.9 %), displacement (44.3 %), and escape (67.6 %). Supplementary Table S1 shows that 16.2 % of students reported needing improvement in academic performance. Students with elevated scores (> 25) in the storage (4.4 %), attention (6.2 %), and executive (4.4 %) domains also reported corresponding complaints (Table S).

Pie chart representation for gender difference among the students

Pie chart illustration of the subjects based on nationality.

Pie chart illustration of the subjects based on universities.

Frequency distribution of students’ response on SMU

According to

Comparison between academic performance and SMU

| Academic Performance Interval | Yes | No | chi-square | P-value | OR | 95% Confidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoccupation | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Good Performance | 85.7% | 82.5% | 1.324a | 0.250 | 1.271 | 0.844 | 1.913 |

| Needs Improvement | 14.3% | 17.5% | |||||

| Tolerance | |||||||

| Good Performance | 86.9% | 83.2% | 1.032a | 0.310 | 1.341 | 0.76 | 2.365 |

| Needs Improvement | 13.1% | 16.8% | |||||

| Withdrawal | |||||||

| Good Performance | 84.8% | 83.4% | .227a | 0.633 | 1.113 | 0.718 | 1.725 |

| Needs Improvement | 15.2% | 16.6% | |||||

| Persistence | |||||||

| Good Performance | 81.8% | 86.9% | 3.242a | 0.072 | 0.680 | 0.446 | 1.037 |

| Needs Improvement | 18.2% | 13.1% | |||||

| Displacement | |||||||

| Good Performance | 80.3% | 86.6% | 5.133a | 0.023 | 0.633 | 0.425 | 0.942 |

| Needs Improvement | 19.7% | 13.4% | |||||

| Problems | |||||||

| Good Performance | 90% | 82.2% | 5.368a | 0.021 | 1.953 | 1.099 | 3.470 |

| Needs Improvement | 10% | 17.8% | |||||

| Deception | |||||||

| Good Performance | 85% | 83.3% | .323a | 0.570 | 1.138 | 0.728 | 1.779 |

| Needs Improvement | 15% | 16.7% | |||||

| Escape | |||||||

| Good Performance | 84.4% | 82.5% | .442a | 0.506 | 1.152 | 0.759 | 1.747 |

| Needs Improvement | 15.6% | 17.5% | |||||

| Conflict | |||||||

| Good Performance | 86.9% | 83.2% | 1.032a | 0.310 | 1.341 | 0.76 | 2.365 |

| Needs Improvement | 13.1% | 16.8% | |||||

Comparison between working memory and SMU

| Working memory | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage Domain | Yes | No | chi-square | P-value | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Preoccupation | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Good | 95.3% | 97.6% | 2.879a | 0.090 | 0.496 | 0.217 | 1.132 |

| Needs Improvement | 4.7% | 2.4% | |||||

| Tolerance | |||||||

| Good | 94.7% | 97.5% | 3.644a | 0.056 | 0.458 | 0.202 | 1.040 |

| Needs Improvement | 5.3% | 3.9% | |||||

| Withdrawal | |||||||

| Good | 94% | 97.8% | 6.865a | 0.009 | 0.349 | 0.154 | 0.793 |

| Needs Improvement | 6% | 2.2% | |||||

| Persistence | |||||||

| Good | 96.1% | 97.5% | 1.020a | 0.312 | 0.633 | 0.259 | 1.547 |

| Needs Improvement | 3.9% | 2.5% | |||||

| Displacement | |||||||

| Good | 95.3% | 97.8% | 3.324a | 0.068 | 0.466 | 0.201 | 1.078 |

| Needs Improvement | 4.7% | 2.2% | |||||

| Problems | |||||||

| Good | 94.7% | 97.2% | 2.378a | 0.123 | 0.511 | 0.214 | 1.217 |

| Needs Improvement | 5.3% | 2.8% | |||||

| Deception | |||||||

| Good | 95.7% | 97.1% | 0.946a | 0.331 | 0.660 | 0.284 | 1.533 |

| Needs Improvement | 4.3% | 2.9% | |||||

| Escape | |||||||

| Good | 96.3% | 97.4% | 0.622a | 0.430 | 0.687 | 0.269 | 1.754 |

| Needs Improvement | 3.7% | 2.6% | |||||

| Conflict | |||||||

| Good | 93.4% | 97.3% | 4.776a | 0.029 | 0.390 | 0.163 | 0.934 |

| Needs Improvement | 6.6% | 2.7% | |||||

Discussion

The present study quantified the prevalence of social-media addiction and investigated its associations with academic performance and working memory among undergraduate students. Patterns of social-media use varied according to participants’ age, gender and geographical origin 34. Consistent with these findings, Meng et al. 35 reported a global upward trend in social-media addiction, which was also evident in our predominantly international sample. Social media exerts a profound influence on individuals and society, shaping perspectives, interpersonal behaviours and interactions across genders 36. It provides a platform for emotional expression and positive reinforcement, but also propagates unrealistic beauty standards and fosters feelings of inadequacy and dominance 3,5,37. Such exposures may elicit social comparison, diminished self-esteem, jealousy and anxiety 38, factors that potentially mediate the development of social-media addiction observed in this cohort.

‘Escape’ behaviour was particularly prevalent among female students. Societal expectations and gender-specific pressures may render female students more vulnerable to stress and anxiety. Escape behaviours include mindless scrolling, online gaming, passive video consumption and seeking validation through ‘likes’ and comments. Accordingly, female students may employ social media as a coping mechanism to obtain psychological relief 39. Male students, however, reported greater ‘conflict’ with family members regarding their social-media use, whereas female students tended to express emotions to avert discord and maintain relationships 40. Prevailing masculinity norms may discourage males from activities perceived as frivolous, thereby reducing the prevalence of escape behaviours in this group 39,41,42. Algorithmic reinforcement, intentionally optimised to prolong user engagement, may exacerbate interpersonal conflict by decreasing receptivity to reasoned discourse and entrenching pre-existing positions. The absence of face-to-face cues on social media can promote misinterpretation and aggressive exchange, further intensifying conflict 43.

Shimoga et al. 44 similarly noted that students who limited social-media time were more likely to engage in productive physical activity, a trend mirrored in our data. In contrast, students reporting no physical activity frequently exhibited symptoms of ‘preoccupation’, ‘tolerance’ and ‘displacement’. Consistent with previous work 45,46, heightened ‘preoccupation’ was associated with extended time spent online. Adverse online interactions may impair concentration, disrupt time management and precipitate procrastination. Platform design, peer influence, escapism, instant gratification and fear of missing out collectively drive excessive use among students 46. A paucity of offline support may lead students to rely on social media as their primary avenue for social interaction. Stress, low self-esteem, inadequate coping strategies, peer influence, anonymity, escapism and attention-seeking behaviour may underlie displacement and problematic use 47.

Our study did not identify a significant association between social media addiction and grade point average (GPA), although students with higher academic performance still reported ‘displacement’ and ‘problems’. Previous research has reported that social media use can negatively affect academic performance by reducing the time available for learning and classroom activities, particularly among students requiring academic improvement 48. The high prevalence of students who reported neglecting other activities to engage with social media may, however, reflect that they also employ these platforms for educational purposes 9. Nevertheless, prolonged daily exposure to social media has been associated with deterioration in academic performance 49. The widespread personalization and modification of social-networking sites among students therefore remains a major concern with respect to their study habits 50.

With respect to cognitive outcomes, our findings indicate that social media addiction did not exert a broad impact on working memory; only ‘withdrawal’ and ‘conflict’ complaints were reported in connection with this domain. These data therefore suggest no direct influence of social media addiction on working memory, although indirect effects mediated by the neglect of essential activities cannot be excluded. A comparable investigation likewise reported that working memory was unlikely to be affected by social media use in healthy participants 35. However, the same study demonstrated that excessive exposure among individuals with psychiatric disorders such as depression can impair working memory—an aspect beyond the scope of the present work 35. Another study observed that memory performance was negatively influenced by social media use, potentially owing to stress-related neurobiological mechanisms 51. Although a large proportion of our participants exhibited adequate working-memory capacity, many still reported ‘withdrawal’ and ‘conflict’, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to preserve and enhance this cognitive function.

Recommendation

Managing social networking addiction requires fostering digital empathy, educating users about its consequences, and establishing a secure online environment that encourages open dialogue and the reporting of abusive behaviour 52. When attempting to reduce screen time, students may experience restlessness, irritability, anxiety, and an intense urge to reconnect, illustrating the addictive cycle and highlighting the necessity for prudent consumption patterns and digital well-being initiatives 53. Excessive engagement can impair academic or occupational performance, raise online-safety concerns, and precipitate additional psychosocial sequelae. Mitigation therefore demands the promotion of responsible online conduct, comprehensive risk education, and the implementation of robust reporting and moderation mechanisms. Educational institutions should promote digital balance, instruct learners in healthy use, facilitate offline social interaction, and strengthen resilience to real-world stressors. Establishing clear boundaries, practising digital self-regulation, and seeking professional support for emotional distress can redirect attention toward more productive pursuits, particularly academic work 54.

While social media offers an easily accessible outlet for relaxation and temporary escape via mobile devices, its benefits are realised only with judicious use; conversely, indiscriminate or excessive use may prove detrimental.

Conclusion

Our study identified physical activity and complaints related to physical displacement and other difficulties as significant predictors of academic performance. Students should be mindful that excessive engagement with social media may substantially impair their studies. Accordingly, access to counselling services is recommended for students reporting such complaints, as early intervention may promote optimal working memory and prevent psychosocial sequelae that were beyond the scope of the present investigation.

This cross-sectional design limits causal inference between social media use disorder, academic performance, and working memory because longitudinal trajectories could not be evaluated. Our statistical approach may also have introduced error, thereby affecting the reliability of the findings. Although the sample encompassed a substantial cohort of students from three universities in Viet Nam’s two most populous cities, generalisation to the entire student population remains restricted; in addition, most participants were international students at various stages of training.

The instruments used to assess social media use, academic performance, and working memory exhibit inherent validity and reliability constraints, which could influence result accuracy. The study systematically applied all nine DSM-5 criteria for behavioural addiction; however, these criteria constitute a subjective self-report scale and did not allow differentiation among specific platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, YouTube), a notable limitation. Moreover, unmeasured confounders may have affected the observed associations. Because data were self-reported, response bias is possible. Finally, we were unable to perform formal clinical diagnoses of addiction owing to the large sample size; nevertheless, the findings underscore the need to raise awareness of social media addiction among university students.

Abbreviations

APS: Academic Performance Scale; BSU: Batumi State University; CI: Confidence Interval; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; EEU: East European University; GPA: Grade-Point Average; OR: Odds Ratio; SD: Standard Deviation; SMU: Social Media Usage (Scale); SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; UG: University of Georgia; UGREC: University of Georgia Research Ethics Committee; WMQ: Working Memory Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

M. E. N: Original draft, conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. M. E. M. and C.P: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. C. R and V. N: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing. Z. N: Original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics council of the University of Georgia (UGREC-31-23).

Informed consent

Comprehensive instruction was provided in the survey including a consent form in which the participant can discontinue the study at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support our findings are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants for the time dedicated to completing this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.